When the Mac Came to Market Street

“Welcome,” a voice rings, “to the 1983 Apple national sales convention.”

Over the next five days, 900 attendees — the Apple sales army, conscripted for the sole purpose of infiltrating an empire — witness the end of an era and the birth of a new entity. The objective is twofold: to convey a plan to penetrate the Macintosh into the retail market and to destroy IBM. And the message, delivered in a manner that is now as iconic as the brand he created, will come not from a gun-slinging sales guru. It will come straight from the top.

When the 900 attendees — jet-lagged — gather in the main auditorium for the opening ceremony, they are suspended as if on tenterhooks by a buzz they can’t quite explain, but sense as potent as gravity. The lights cut. The Flashdance theme cues. The lyrics are prophecy: “What a feeling/I can have it all/I can really have it all.”

A multicolored laser show erupts from above, bathing bodies in all colors of Apple iconography. Then … darkness. Deliberate, quiet. A solitary figure walks on stage, cloaked in a spotlight he will come to embrace and shun in equal measure for nearly 30 years. By his side is the Macintosh 128K. The applause is deafening.

“Hi, I’m Steve Jobs.”

Jobs, the boy wonder, proceeds with a compelling history of the microcomputer — from the IBM to the Apple II. He frames the narrative as a struggle between empire and rebellion. Apple, he explains, is now a $300 million corporation and IBM is its strongest competitor. “Apple is perceived to be the only hope to offer IBM a run for its money,” he says. “IBM wants it all and is aiming its guns on its last obstacle to industry control: Apple. Will Big Blue dominate the entire computer industry? The entire information age? Was George Orwell right about 1984?”

The lights dim again. A screen illuminates and Ridley Scott’s famous “1984” commercial, Macintosh’s dazzling coming-out, glows gray and foreboding. An army of drones marches across the bleak bowels of an evil empire and sit in pews before a cold, gray monitor. A bespectacled Big Brother spews oligarchy: “We shall prevail.”

But there is hope. A woman, blonde, fit, dressed in red and white, sprints heroically down a narrow corridor holding what appears to be the hammer of Thor. She stops, poised, and heaves it at the screen. The sound of the explosion is anemic compared to the roar of applause.

The commercial, which premieres globally during the Super Bowl halftime show on January 22, 1984, ends with another prophecy: “On January 24, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like 1984.”

Two days later, Apple dispatches its first official press release introducing the Macintosh. Buried in the text is the first mention of what will come to be known as the Apple University Consortium.

“Twenty-four of the nation’s leading universities … Harvard, Princeton, Stanford and Yale, have joined forces with Apple to plan and implement personal-computer applications over the next few years.”

Absent from the list is Drexel University, the first member of the consortium to require every student to use the Macintosh.

By January 1984, Drexel University had already cut its own slice of the Apple pie and was anxiously waiting to serve it on a silver platter. Rumor had it that each unit would be embossed with a blue “D” for Drexel. They would become known in the corridors of Matheson and Main as the “DUs.”

Back in the fall of 1982, one year before the sales meeting in Hawaii, Drexel University President William Walsh Hagerty — who in 1970 steered Drexel through its transition from an institute of technology to university status — announced that personal microcomputer access would be mandatory for every newly enrolled freshman beginning with academic year 1983–1984. Furthermore, all academic departments were expected to incorporate microcomputing into their curricula. After two decades of unparalleled growth, during which President Hagerty oversaw the formation of the College of Science and the College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Drexel was no longer a regional hub for experiential education; Drexel was finally an underdog contender at the national level.

In Going National, the aptly named 1985 documentary that charts the rise of the microcomputer at Drexel, Bernard Sagik, Ph.D., then vice president for academic affairs — the man who first suggested the idea of microcomputing to Hagerty — explains that going national meant competing against all first-rate institutions and finding the right fulcrum, the perfect message, to make the endeavor worthwhile.

“I felt we had to trade on what Drexel had already — that was unique to us — which means co-op, very applied programs built on a solid theoretical base. These are the things that we can sell,” he says in the film.

At the time, some faculty had to be told that the mouse was not of the rodent persuasion, but was, rather, a device for navigation.

At the time, Drexel was still contracting outside vendors for its computing needs. The mainframe and punch card were standard technology, a disconnect that not only demanded attention, but necessitated a monumental change: Going national meant adapting academic microcomputing. For all.

“The more you looked at it the more you realized you could not build strength in what was going to be the area of the next two decades … automation, robotics, computer applications … going off-campus,” Sagik says.

Hagerty, serving his final term as Drexel’s executive-in-chief, agreed, and was willing to hang his presidency on it. A committee was formed, including Hagerty; Sagik; Brian L. Hawkins, then assistant vice president for academic affairs; and Thomas Canavan, dean of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences. A contract — now lost, perhaps in the bowels of the library that bears the Hagerty name — was agreed upon between Drexel and Apple Inc. The deal included a nondisclosure clause, typical of Jobs and his compulsive confidentiality, which legally bound the committee to keep quiet until the launch.

“The secrecy was totally contrary to the academic process,” Hawkins, who was named director of the Drexel Microcomputing Program, and would later found EDUCAUSE, a nonprofit that promotes the intelligent use of technology in education, says in Going National.

But keeping mum didn’t mean keeping quiet. In typical Drexel fashion, the administration began educating faculty and students on the yet-to-be-named microcomputer. Hawkins held “Microcomputing Information Sessions” in Patton Auditorium to address the growing list of concerns. How will microcomputing change education? Will Pascal be the programming language? Bound by nondisclosure, Hawkins could do little to assuage the apprehension. “The machine is not meant to change the curriculum, but to enhance the curriculum,” he says in a particularly heated scene in Going National.

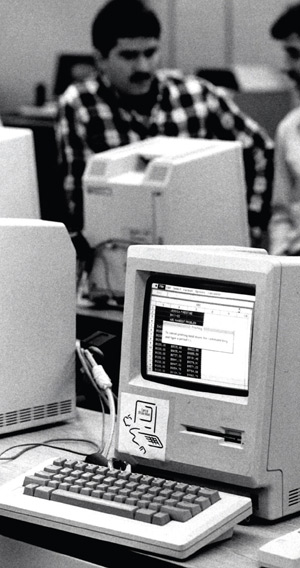

By the fall of 1983, just as Jobs addressed his troops in Waikiki, the Trek Building, located at 32nd and Race Street, had been renovated to facilitate the influx and distribution of approximately 2,000 nameless, top-secret Apple computers. A state-of-the-art computer classroom was installed in the Korman Center; a group called DUsers, comprising students with microcomputer experience, was convened to help the uninitiated. A newsletter called boot was conceived and edited by Professor Tom Hewett to address the pressing issues of the microcomputer user.

Just before the launch, a group of graduating seniors was given access to a roomful of covered computers with no visible labels. They poked around, played with the graphic user interface, saved files on strange floppy disks. Afterward, they were administered a test to assess the effects of microcomputing on stress and anxiety, stratified by age, gender and academic major. The results were clear: Drexel was ready.

On March 2, 1984, The Triangle student newspaper’s front-page headline read: “Macintoshes arrive on campus; distribution will begin Monday.” There was extra security guarding the Trek Building. Trucks rolled in from Market Street with cargo locked so tight with steel rope that hacksaws and chain-cutters were necessary to extract the spoils. And as the first white boxes, each affixed with a Matisse-like portrait of the hardware inside, were loaded into the warehouse, fingers were crossed particularly tight back at 3141 Chestnut.

And so it was that, on March 5, 1984, some three years after President Hagerty’s prophetic announcement, 1,850 Drexel freshmen trudged up 32nd Street in the cold to pick up their very own Macintosh 128K.

The rumors were true. Each computer was embossed with a blue “D” for Drexel. The price? $1,000, plus tax. Not bad for a unit that sold for $2,495 retail. The 20-pound package included MacWrite, MacPaint and Microsoft Multiplan software, designed by some nerd named Bill Gates. Each box contained the CPU, a keyboard and a mouse. At the time, some faculty had to be told that the mouse was not of the rodent persuasion, but was, rather, a device for navigation.

While Jobs’ grand scheme to take down Big Blue ultimately came true, the deciding battleground would not be in the conference rooms of corporate America, but in the halls and homes of academia. Students and educators became the force that sacked the IBM Empire. Sheldon Master, who in 1984 was a 30-year-old recruit at that first national sales meeting, and is now president/owner of audiovisual tech firm Haddonfield Micro Associates, remembers that while the Waikiki call to arms was lofty — a true David and Goliath tale — the story didn’t play out as planned. “Empires aren’t toppled head-on,” he says. “They’re taken out on the peripheries. Apple wanted to crack into corporations through desktop publishing. What wound up happening was that we broke into homes.”

Now, 28 years after the birth of the product he helped launch — that built his career — Master reads the Cupertino press release announcing the Macintosh, reciting sections from memory: “… a sophisticated, affordably priced personal computer designed for business people.” He stops on the third page. “Here,” he says, pointing to bold text that reads Macintosh Sales Outlook. “Let me show you something.”

In the release, a third-party analyst firm estimated global sales for the Macintosh to total 350,000 units in 1984: 70 percent from businesses, 20 percent from colleges and universities and 10 percent from home users.

“It didn’t happen like that,” Master says. “Probably more like 40 percent went to businesses, about 40 percent went to education and 20 percent to home users. Dealers were selling to schools, homes and then businesses. Education was the most important.

“Those students eventually made it into the workforce. And what computer do you think they brought with them? The Mac. It was brilliant. The educational consortium launched Apple into the business market.

“The consortium was based on respect, and Jobs had a lot of respect for Drexel,” Master says. And so, as Apple rode a tsunami of success that has yet to be rivaled, Cupertino began passing out buttons that triumphantly read: “IBM — I’ll Buy Mac.”

Meanwhile, Drexel began the process of adapting the Macintosh into its curricula. The microcomputer forced educators to re-evaluate how they delivered their message to students who, in large measure, were infinitely more familiar with the medium.

“The Macintosh caught on almost instantly,” remembers Provost Mark L. Greenberg, then an untenured assistant professor of English. “And, in typical fashion, the students were probably ahead of the faculty. The melding of technology and higher education occurred at Drexel within the first year. And we never looked back.”

Even the humanities and social sciences caught on. A history professor began developing the first electronic atlas; and scientists, engineers and accountants built math modules that simplified coursework. English students, no longer bound by pen and typewriter, began fine-tuning syntax with MacWrite’s editing interface. Provost Greenberg even contributed an essay musing about the implications of the microcomputer for writers. Would the keyboard and mouse change the craft? Would intimacy be lost?

By the winter of 1985, the Macintosh was everywhere. The DUsers began publishing a newsletter called C⌘MMAND. DUTalk, a “terminal emulation package” that facilitated communication among multiple computers, was given away for free in the Korman Center. Drexel’s first-ever MacFair took place in April. The first “Micro Hotline” began operation: the number is now Drexel IRT’s extension.

According to Christopher Laincz, Ph.D., who attended Drexel soon after the arrival of the Macintosh and is now an associate professor of economics at LeBow, being exposed to the microcomputer gave students advantages that reverberated beyond the walls of academia.

“We were familiar with basic computer software,” he says. “As we left the University, I’d venture that 90 percent of us were working with computers. Studies have shown that at that time … there was a computer usage premium in wages. People who worked with computers had about 10 to 15 percent higher wages than other people, controlling for all other factors that could explain wage differential. That was a huge benefit for us.”

While the Jobs legend has been canonized, Drexel’s own visionaries — namely Sagik and Hagerty — now endure on weathered bronze plaques and in black-and-white photographs.

“Bernie Sagik was a cultured, articulate, accomplished scientist and educator,” says Greenberg. “A model academic. He thought about the computer as a teaching, learning and research tool — and instantly saw its applicability to the mission of higher education.

“However, William Hagerty needed the insight, brains and guts to commit. I would have loved to be a fly on the wall when Bernie Sagik came to Hagerty with the idea.”

On Saturday, March 9, 1985, just one year after the Macintosh arrived, Drexel University hosted a black-tie world premiere of Going National in the Mandell Theater and James Creese Center. Jobs was among the distinguished guests.

After the viewing, dressed in a smart tuxedo and noticeably pleased by what he’d seen, what he’d started, Jobs spoke, calling Drexel “a pioneer for being the first university to fully incorporate the Macintosh” into its curricula.

“He sees the relationship between Drexel and Apple as only the beginning [of] a future of new and better education through the development of high technology,” read the coverage in COMMAND.

For Drexel, a school so devoted to mingling technology and education, Jobs’ visit was not just another victory lap; it was a homecoming. “As we talk about the character of Drexel,” says Greenberg, “the idea that we are risk takers, that we are forerunners, that we are innovators — this is no better exemplified than by the adoption of that microcomputer. And at a time when most people didn’t even know what it was.”